Switching from a brand-name NTI drug to a generic version sounds simple-cheaper, same active ingredient, right? But for drugs with a Narrow Therapeutic Index, that small change can mean the difference between stable health and a life-threatening event. NTI drugs have a razor-thin margin between the dose that works and the dose that harms. Even a 10% shift in blood levels can trigger seizures, organ rejection, or dangerous bleeding. And yet, across the U.S. and Australia, these switches happen daily, often without warning.

What Makes a Drug 'Narrow Therapeutic Index'?

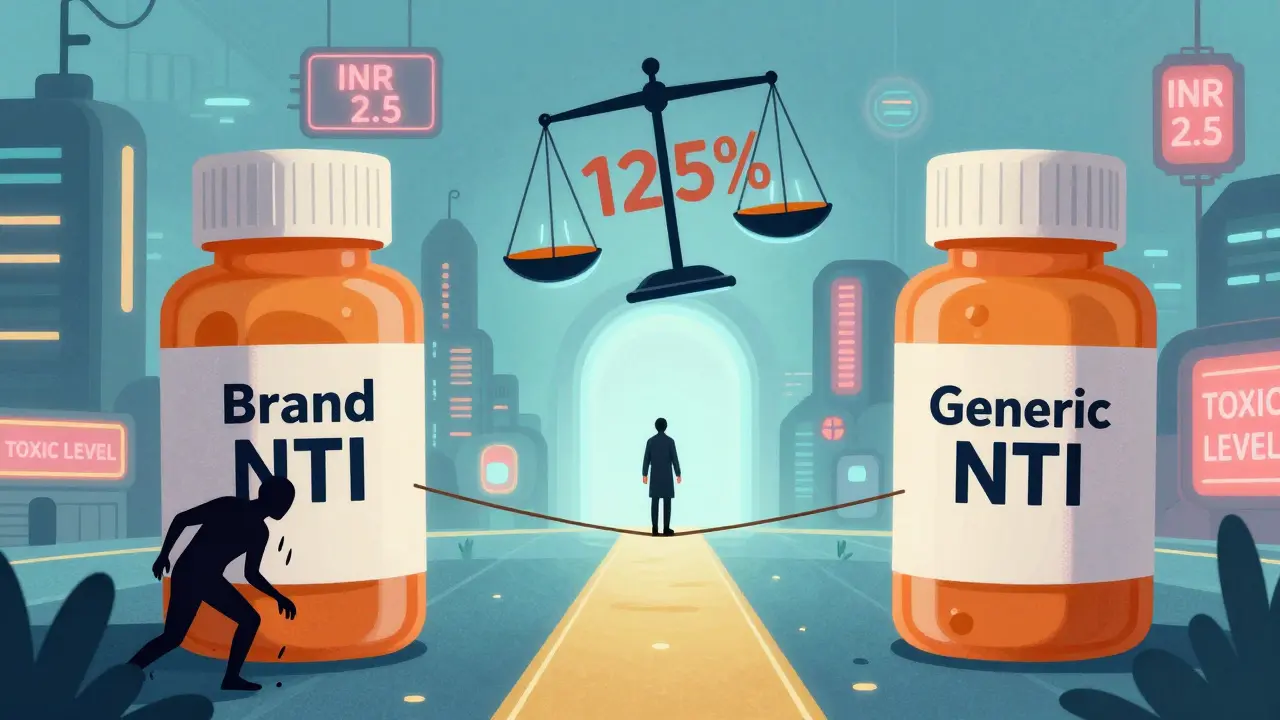

NTI drugs aren’t just any medications. They’re the ones where your body’s response is extremely sensitive to tiny changes in concentration. The FDA defines them as drugs where small differences in dose or blood levels can cause serious harm-like organ failure, uncontrolled seizures, or fatal bleeding. Think of it like walking a tightrope: too little, and the treatment fails. Too much, and you overdose. The therapeutic window is often less than a 2-fold difference between the minimum effective dose and the minimum toxic dose.

Common NTI drugs include warfarin (blood thinner), phenytoin and levetiracetam (anti-seizure meds), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), digoxin (heart medication), cyclosporine and tacrolimus (transplant immunosuppressants), and amiodarone (anti-arrhythmic). These aren’t optional medications-they’re life-sustaining. A patient on cyclosporine after a kidney transplant doesn’t just take it to feel better; they take it to keep their new organ from being rejected.

How Are Generics Approved? The 80-125% Rule

Here’s the problem: regulators in the U.S. allow generic drugs to be 80% to 125% as bioavailable as the brand-name version. That’s a 45% range. For most drugs, that’s fine. For an NTI drug? It’s a gamble.

Imagine you’re on brand-name warfarin, and your INR (a measure of blood clotting) is perfectly stable at 2.5. You switch to a generic that’s 125% bioavailable. Your blood levels jump 25%. Your INR spikes to 4.0. You’re at risk of internal bleeding. Now imagine switching to a generic that’s only 80% bioavailable. Your INR drops to 1.8. You’re at risk of a stroke. Both scenarios happen. And because the FDA treats all generics the same way, even NTI drugs get the same broad allowance.

Other countries see it differently. Canada and the European Medicines Agency require tighter limits: 90% to 111% for NTI drugs. That’s a 21% range-not 45%. Why? Because they’ve seen the data. And they’ve chosen to protect patients over cost savings.

Warfarin: The Most Common NTI Switch

Warfarin is the most frequently substituted NTI drug. About 48% of NTI prescriptions in the U.S. are for warfarin. It’s cheap, widely used, and often switched without much thought. But the evidence is mixed.

Observational studies show that after switching to generic warfarin, nearly 40% of patients experience worse INR control. One study found only 28% stayed within 10% of their target INR after the switch. That means more doctor visits, more blood tests, more anxiety. But here’s the twist: randomized controlled trials-the gold standard-show no significant difference in bleeding or clotting events between brand and generic warfarin.

So what’s going on? It might be that the brand-name version is more consistent batch to batch. Or that pharmacists and patients are more careful when they know it’s brand-name. Or that patients who switch are more likely to be on unstable regimens to begin with. Either way, most experts agree: if you switch warfarin, monitor your INR closely for the next few weeks.

Antiepileptic Drugs: When a Switch Means a Seizure

This is where things get scary. For patients with epilepsy, a switch to a generic antiepileptic can mean a return to seizures. And not just any seizures-tonic-clonic, status epilepticus, injuries from falls, ER visits.

A study of 760 epilepsy patients found that many who switched to generic levetiracetam or phenytoin reported increased seizure frequency, blurred vision, memory loss, depression, and aggression. One physician survey documented 50 patients who had breakthrough seizures after switching. Nearly half of them had lower drug levels at the time of the seizure.

Phenytoin is especially problematic. Studies show generic versions can be 22% to 31% less bioavailable than the brand. That’s not a rounding error-that’s a clinical disaster. In some states, laws prohibit automatic substitution of antiepileptic drugs. But in others, pharmacists can switch without telling the patient or doctor. And many patients don’t realize their medication changed until they have a seizure.

Immunosuppressants: The Silent Threat After Transplant

For transplant patients, generic cyclosporine or tacrolimus isn’t just about cost-it’s about survival. One study found that 17.8% of kidney transplant patients needed a dose adjustment within two weeks of switching from Neoral (brand) to a generic. Trough levels jumped from 234 ng/mL to 289 ng/mL. That’s a 23% increase. Too much? Toxicity. Too little? Rejection.

Reddit threads from transplant communities are filled with stories: “Switched to generic cyclosporine, had rejection in 3 weeks.” “My creatinine spiked after the pharmacy changed my med.” Others say, “No issues for five years.” The inconsistency is the problem. Two different generic manufacturers might both be “AB-rated,” but their formulations vary wildly. One batch of Mylan tacrolimus had active ingredient levels from 100% to 120%. Another, from Accord, ranged from 86% to 99%. That’s a 34% difference between generics. If you switch from one generic to another, you’re still playing Russian roulette with your organ.

What Do Pharmacists and Doctors Really Think?

A 2019 FDA survey of pharmacists found that 87% believed generic NTI drugs were just as effective as brand-name. 94% said they were equally safe. But here’s what they didn’t say: 41% recommended extra monitoring after switching. For antiepileptic drugs, 62% expressed serious concerns about seizure control.

Doctors, especially neurologists and transplant specialists, are far more cautious. Many refuse to allow substitutions unless the patient has been stable on the same brand for years. Some only prescribe brand-name for NTI drugs. Others require written consent before switching. But in many clinics, the decision is made by the pharmacy-not the prescriber.

What Should You Do If You’re on an NTI Drug?

Here’s what works in real life:

- Know your drug. Is it on the NTI list? Warfarin? Phenytoin? Cyclosporine? If yes, treat it differently.

- Ask your pharmacist. “Is this the same brand I’ve been taking?” Don’t assume. Ask every time you refill.

- Check your levels. For warfarin, get an INR test 7-14 days after any switch. For cyclosporine or tacrolimus, ask for a trough level check at 2 and 4 weeks. For phenytoin, get a serum level test within a week.

- Track symptoms. If you feel different-more fatigue, more seizures, unusual bruising, nausea, confusion-don’t wait. Call your doctor. It might be the drug.

- Request brand-name if needed. If you’ve had problems before, ask your doctor to write “Dispense as written” or “Do not substitute.” In many places, that’s legally binding.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Generic drugs save billions. That’s good. But when it comes to NTI drugs, the cost of a mistake isn’t financial-it’s human. A single seizure, a rejected kidney, a stroke-all preventable with better rules.

The FDA is starting to catch up. In 2022, they released draft guidance proposing product-specific bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs. That means warfarin might get different rules than tacrolimus. That’s progress. But until then, the burden falls on patients and providers.

Industry analysts predict a 15-20% rise in therapeutic drug monitoring for NTI drugs over the next five years. That’s not because people are getting sicker-it’s because we’re finally realizing that not all generics are created equal. And for some drugs, that difference can kill.

What’s Next?

Research is moving toward personalized dosing-using genetics to predict how someone metabolizes drugs like warfarin or phenytoin. Clinical trials are underway to see if genetic testing can prevent substitution-related problems. But that’s years away.

For now, the best protection is awareness. If you’re on an NTI drug, don’t let convenience override caution. Your life isn’t a cost-saving experiment. It’s your life.

gary ysturiz

Just had to switch my dad’s warfarin last month. Got his INR checked a week later-spiked to 4.2. We were lucky it didn’t turn into a disaster. Now we always ask for the brand. It’s not about being expensive, it’s about not ending up in the ER.

jordan shiyangeni

It’s pathetic that the FDA lets this happen. We’re talking about people’s lives here-not some commodity to be optimized for profit. The 80-125% rule is a joke. If you’re going to sell a drug that can kill you if the dosage is off by 5%, you better make sure it’s identical. The fact that we allow this in America while Europe and Canada have stricter standards says everything about our priorities. Corporate greed over human life. Again.

Abner San Diego

Ugh. Another one of these ‘generic drugs are evil’ rants. Wake up. We’re not in Canada. We’re in the US. Cheaper meds mean people can actually afford to live. You want brand-name warfarin? Pay $200 a month. Or get your ass to a clinic and take the generic like everyone else. Stop acting like your life is more important than the 50-year-old single mom who can’t afford insulin.

Eileen Reilly

my doc switched me to generic levetiracetam and i swear i felt like i was drunk for 2 weeks. brain fog, mood swings, like my thoughts were underwater. i went back to brand and boom. normal again. pharmacy didn’t even tell me they switched it. smh.

Monica Puglia

Thank you for writing this. 🙏 I’m a transplant nurse and I’ve seen too many patients panic when their tacrolimus gets switched without warning. One guy’s creatinine jumped from 1.3 to 2.8 in 10 days. He thought he was just ‘getting sick.’ It was the generic. We had to rush him back in. Please, if you’re on an NTI drug-ask. Check. Track. You’re not being paranoid. You’re being smart.

Cecelia Alta

Oh my god. I’m 32 and on cyclosporine after a liver transplant. My pharmacy switched me to a different generic last year. I didn’t notice until I started losing hair and my hands shook all day. My doc said my levels were ‘fine’ but I knew something was off. I went to a different pharmacy and asked for the original brand. I haven’t had a single symptom since. Why is this so hard? Why do I have to fight just to stay alive? And now they’re trying to make me switch again. I’m done. I’m paying out of pocket. My life isn’t a cost-cutting experiment.

steve ker

US FDA is broken. Europe does it right. End of story

George Bridges

My sister’s a neurologist. She told me that in her clinic, they only allow generic AEDs if the patient has been stable on the same generic for over a year. And even then, they test levels. I didn’t realize how much of a minefield this was until she explained it. We assume meds are interchangeable. They’re not. Not all of them.

Faith Wright

So let me get this straight… the system lets pharmacists swap life-saving meds without telling you, and then expects you to notice you’re having seizures or bleeding internally? And the solution is… more blood tests? More doctor visits? More anxiety? This isn’t healthcare. This is a trap.

Rebekah Cobbson

If you’re on an NTI drug and you’ve never asked your pharmacist if your med changed-you’re not alone. But you can change that today. Write ‘Dispense as Written’ on your prescription. Keep a little card in your wallet that says your drug and what brand you’re on. Call your doctor if you feel ‘off.’ You’re not being dramatic. You’re being your own best advocate. And that matters more than you know.

Write a comment