When your doctor orders a brain MRI, it’s not because they’re being overly cautious-it’s because they need to see what’s happening inside your skull in a way no other test can. Unlike X-rays or CT scans, MRI doesn’t use radiation. Instead, it uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create detailed pictures of your brain’s soft tissues. This makes it the gold standard for diagnosing conditions like multiple sclerosis, strokes, tumors, and even early signs of dementia. But what do those images actually show? And how do doctors tell the difference between normal aging and something serious?

What You’re Really Seeing on a Brain MRI

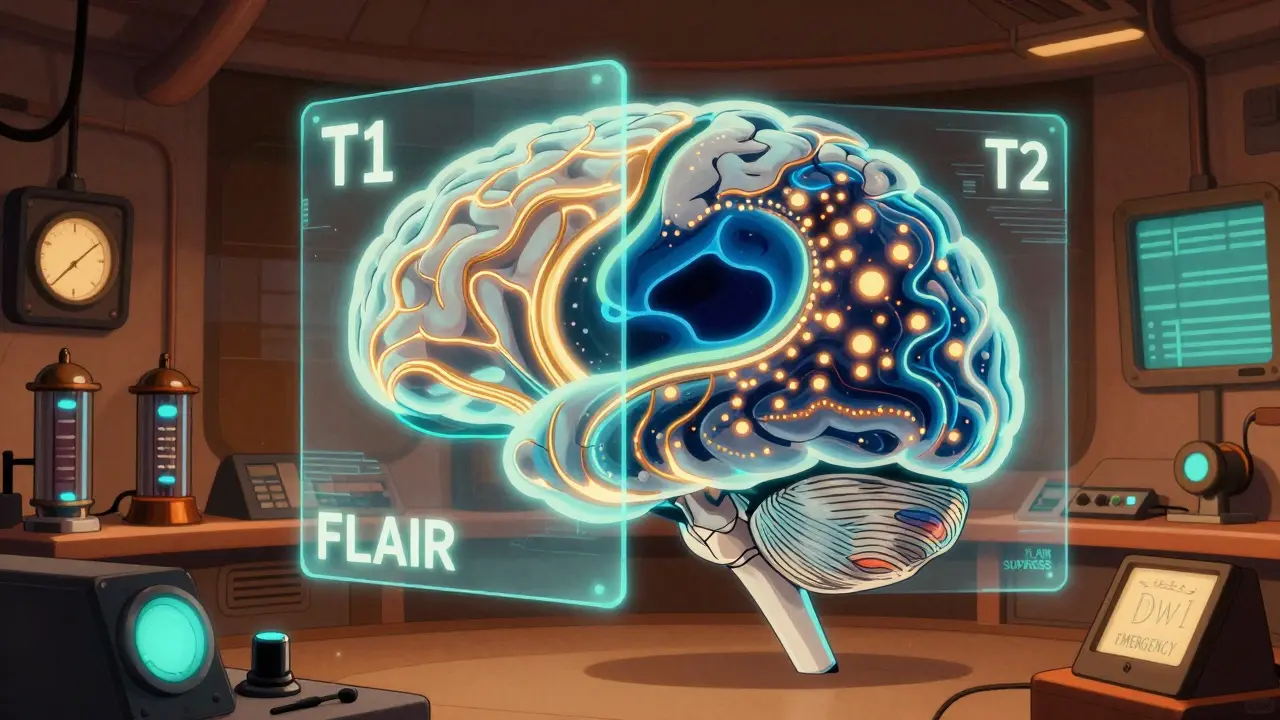

A brain MRI doesn’t give you one picture-it gives you several, each highlighting different things. These are called sequences, and each one acts like a different filter. Think of them as taking multiple photos of the same room with different lighting: one shows shadows, another highlights reflections, another reveals hidden textures.

The most common sequences are T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR, DWI, and SWI. On a T1 scan, fat and some types of tissue appear bright white, while fluid like cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) looks dark. This is great for seeing anatomy-where the brain’s gray and white matter meet, how big the ventricles are, whether the brainstem looks normal.

T2-weighted images flip that: water becomes bright. That means swelling, inflammation, or old injuries show up clearly. But here’s the catch: CSF also lights up on T2, so if you’re looking for a small lesion near a ventricle, you might miss it because the fluid is just as bright as the problem. That’s where FLAIR comes in. FLAIR suppresses the CSF signal, making it dark again, while keeping abnormal tissue bright. This is why neurologists rely on FLAIR to spot multiple sclerosis plaques, tiny strokes, or infections near the brain’s fluid spaces.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is the emergency tool. If someone walks into the ER with sudden weakness or slurred speech, DWI can show a stroke within minutes. It detects when water molecules in brain tissue can’t move freely-something that happens right after blood flow stops. A low ADC value (below 600 x 10^-6 mm²/s) confirms an acute infarct. CT scans can take hours to show this. MRI catches it before the damage becomes permanent.

And then there’s SWI or gradient echo. These sequences are sensitive to blood. Even tiny amounts of old bleeding-like from a microhemorrhage-show up as dark spots. This matters because repeated microbleeds can signal high blood pressure damage, amyloid angiopathy, or even early Alzheimer’s. A single spot might mean nothing. Three or four in the same area? That’s a pattern.

Common Findings and What They Mean

Not every bright spot on an MRI is a crisis. In fact, many are just part of aging-or even normal variation.

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are one of the most common findings. These are small, bright areas near the brain’s ventricles, often seen on FLAIR or T2 scans. In people under 50, about 15% have them. By age 70, that jumps to 90%. They’re linked to small vessel disease-tiny blood vessels in the brain narrowing over time due to high blood pressure, diabetes, or just aging. Most people with these don’t have symptoms. But if they’re widespread, especially in the deep white matter, they can raise the risk of future stroke or cognitive decline.

Then there’s atrophy. That’s when the brain shrinks. Some shrinkage is normal with age. But if the hippocampus (the memory center) is noticeably smaller than expected for your age, it could point to early Alzheimer’s. If the whole brain is shrinking faster than it should, it might be something like frontotemporal dementia or even long-term alcohol use.

Lesions in the periventricular area-right around the fluid-filled spaces-are classic for multiple sclerosis. They’re usually oval-shaped, perpendicular to the ventricles, and show up bright on FLAIR. If you see more than three, especially with spinal cord lesions, the odds of MS go up significantly. But not every lesion is MS. Lyme disease, vasculitis, or even migraines can cause similar patterns. That’s why doctors don’t diagnose MS from one scan alone-they look at symptoms, blood tests, and sometimes spinal fluid.

Incidental findings are another big part of MRI. You might get a scan for headaches, and the radiologist spots a small, slow-growing tumor on the nerve that connects your ear to your brain-a vestibular schwannoma. These are usually benign, grow slowly, and may never need treatment. But catching them early means you can monitor them instead of waiting for hearing loss or balance problems to develop.

When MRI Is the Right Choice-and When It’s Not

Not every headache needs an MRI. In fact, the American College of Radiology says MRI is usually not appropriate for people with typical migraines and no neurological signs. Studies show only about 1.3% of brain MRIs done for simple headaches find something serious. That’s why doctors follow strict guidelines: if you have a new, severe headache with vomiting, vision changes, seizures, or weakness, then yes, get the scan. If you’ve had the same type of headache for 20 years and it’s just getting a little worse? Probably not.

For acute trauma-like after a car crash or fall-CT is faster. It takes five minutes to rule out a skull fracture or major bleed. MRI takes 30 to 45 minutes. In an emergency, speed saves lives. But if someone is stable and still confused after a head injury, MRI can pick up tiny tears in brain tissue (diffuse axonal injury) that CT misses entirely.

And for stroke? Time is brain. If you’re within the 4.5-hour window for clot-busting drugs, CT is the first step-it rules out bleeding fast. But if the CT is normal and symptoms persist, MRI with DWI is the next move. It can confirm a stroke even when CT looks clean.

What MRI Can’t Tell You

One big limitation: MRI can’t always tell you how old a lesion is. A bright spot on FLAIR could be from a stroke that happened yesterday-or ten years ago. Without contrast (a dye injected into your vein), it’s hard to tell. Contrast helps show active inflammation or tumors because it leaks out of damaged blood vessels. But even then, it’s not perfect.

Another issue: MRI doesn’t show brain function. It shows structure. So if someone has memory problems but their MRI looks normal, that doesn’t mean nothing’s wrong. They might have early Alzheimer’s with no visible plaques yet, or a chemical imbalance like low serotonin. That’s where cognitive testing, blood work, and sometimes PET scans come in.

And then there’s the noise. MRI machines are loud. You have to lie still for half an hour. People with claustrophobia struggle. Open MRIs exist, but they’re lower strength (usually 1.0T or less), so the images aren’t as sharp. For detailed brain work, you need a closed 1.5T or 3.0T machine. The 3.0T gives clearer images, especially for small nerves or early MS plaques, but it’s more sensitive to motion. If you move, the image blurs.

How Radiologists Read These Scans

There’s a method to how they look at it. They start in the middle: the ventricles, the brainstem, the cerebellum. Then they move outward-checking the basal ganglia for tiny old strokes, the white matter for lesions, the cortex for thinning or swelling. They compare both sides. The brain isn’t perfectly symmetrical, but big differences matter. One side larger? Could be a tumor. One side darker? Could be a bleed.

They also look for what’s missing. Are the sulci (the grooves on the brain’s surface) wider than they should be? That’s atrophy. Are the ventricles enlarged? That’s often a sign of fluid buildup or brain shrinkage. Are there dark spots in the cerebellopontine angle? That’s where vestibular schwannomas hide.

And they watch for traps. Flow voids-dark lines where blood rushes through big vessels-are normal. But new radiologists sometimes mistake them for holes or tumors. That’s why training takes months. Even experienced ones double-check: “Is this a lesion… or just a blood vessel?”

What’s Next for Brain MRI?

The field is moving fast. New AI tools can cut scan time in half without losing detail. Some machines now use machine learning to automatically detect early signs of Alzheimer’s by measuring hippocampal volume or spotting subtle texture changes in the cortex. Quantitative MRI-measuring actual numbers like water content or blood flow-is becoming more common in research centers. In the next few years, we’ll likely see these tools used in routine clinics to track progression of diseases like MS or Parkinson’s more precisely.

Ultra-high-field 7.0T scanners are still rare, but they’re showing us brain layers we’ve never seen before. They’re not for everyone-too noisy, too expensive-but they’re helping researchers understand how diseases start at the cellular level.

Still, the basics haven’t changed. MRI remains the best tool we have to see inside the living brain without cutting it open. It doesn’t give all the answers-but it gives the clearest picture of where to look next.

Can an MRI detect Alzheimer’s disease?

MRI can’t diagnose Alzheimer’s on its own, but it can show signs that strongly suggest it. The most common finding is shrinkage in the hippocampus and other memory-related areas. While this also happens with normal aging, the pattern and speed of shrinkage help doctors differentiate. MRI is often used alongside cognitive tests and sometimes amyloid PET scans to confirm the diagnosis.

Why do I need contrast for some brain MRIs?

Contrast dye highlights areas where the blood-brain barrier is broken-something that happens with tumors, infections, or active inflammation like in multiple sclerosis. Without contrast, these areas might look like normal tissue or old scars. Contrast helps doctors tell if a lesion is new and active or something stable from years ago.

Are brain MRI results always accurate?

MRI is highly accurate for detecting structural abnormalities, but interpretation matters. A bright spot could be a tumor, a stroke, or just a normal variant. Radiologists use experience, comparison with past scans, and clinical context to make sense of findings. Sometimes a second opinion is needed, especially for unclear or rare findings.

Can I have an MRI if I have metal implants?

It depends. Pacemakers, cochlear implants, and some older aneurysm clips are absolute contraindications because they can move or heat up in the magnetic field. But many modern implants-like joint replacements, dental fillings, or newer cardiac devices-are MRI-safe. Always tell your doctor and the MRI tech about any metal in your body. They’ll check the specific model before proceeding.

How long does a brain MRI take?

A standard brain MRI takes 30 to 45 minutes. If contrast is needed or if the scan includes special sequences like DTI or SWI, it can take up to an hour. You need to lie very still-any movement can blur the images and make them harder to read.

Is a 3.0T MRI better than a 1.5T?

Yes, for most neurological cases. A 3.0T machine has about 40% more signal than a 1.5T, which means clearer images of small structures like cranial nerves, tiny tumors, or early MS plaques. But it’s also more sensitive to motion and can create more artifacts. For routine scans, 1.5T is still excellent. The choice depends on the clinical question and available equipment.

Beth Cooper

Okay but have you ever heard of the CIA using MRI to implant thoughts? I read on a forum that they reverse-engineered the magnetic pulses to make people see things that aren’t there. That’s why they always make you lie still-it’s not just for image quality, it’s to prevent you from resisting the signal. I mean, why else would they need such expensive machines just to check for ‘tiny strokes’? 🤔

Write a comment