Did you know that in 1989 a painkiller arrived that could knock out moderate‑to‑severe post‑surgical pain almost as fast as an opioid, yet without the addictive cloud? That drug was Ketorolac Tromethamine, a non‑opioid analgesic that reshaped how surgeons manage pain in the recovery room.

Key Takeaways

- Ketorolac tromethamine was discovered in the early 1970s by Searle and approved by the FDA in 1989.

- It works by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, reducing prostaglandin‑driven inflammation and pain.

- Its potency rivals morphine for short‑term use, but it carries risks of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment.

- Intravenous and intramuscular forms allow rapid pain control in hospitals, while oral tablets serve outpatient needs.

- Current guidelines restrict use to five days or less; newer NSAIDs and multimodal protocols have reduced its dominance.

Early Discovery: The Search for a Stronger NSAID

Back in the late 1960s, researchers were busy expanding the family of NSAIDs. Aspirin had proven its worth, but its anti‑platelet effect limited dosing for pain. The goal was clear: find a non‑steroidal compound that could deliver higher analgesic potency without the gastric ulcer fallout.

Scientists at Searle synthesized a series of pyrroloxyl derivatives. One of them, later named ketorolac, showed an impressive ability to inhibit inflammation in animal models. By 1972, the molecule’s structure was locked down, and the name “ketorolac tromethamine” reflected its crystalline salt form designed for better solubility.

From Lab Bench to Clinical Trials

Pre‑clinical studies revealed that ketorolac was about ten times more potent than traditional NSAIDs such as ibuprofen. The next challenge was proving it could relieve pain in humans without the severe side effects that plagued earlier drugs.

PhaseI trials in the mid‑1970s focused on safety and pharmacokinetics. Researchers observed a rapid onset-pain relief began within 30minutes of IV administration-and a half‑life of roughly 5hours, ideal for short‑term postoperative analgesia.

PhaseII and III trials expanded to surgical patients. In a landmark 1985 study, patients receiving ketorolac after abdominal surgery reported pain scores comparable to those given morphine, but with less sedation and faster ambulation. These results set the stage for regulatory review.

Regulatory Milestone: FDA Approval

When the data reached the FDA in the late 1980s, the agency faced a dilemma. On one hand, a powerful new analgesic could reduce opioid consumption; on the other, the same COX inhibition raised flags about gastrointestinal bleeding.

After a series of advisory committee meetings, the FDA approved ketorolac tromethamine in 1989 for short‑term, moderate‑to‑severe pain, but with strict labeling: limit use to five days, avoid concurrent high‑dose aspirin, and monitor renal function. The approval sparked rapid adoption in hospitals worldwide, especially in orthopedic and dental surgery where quick, potent pain control was crucial.

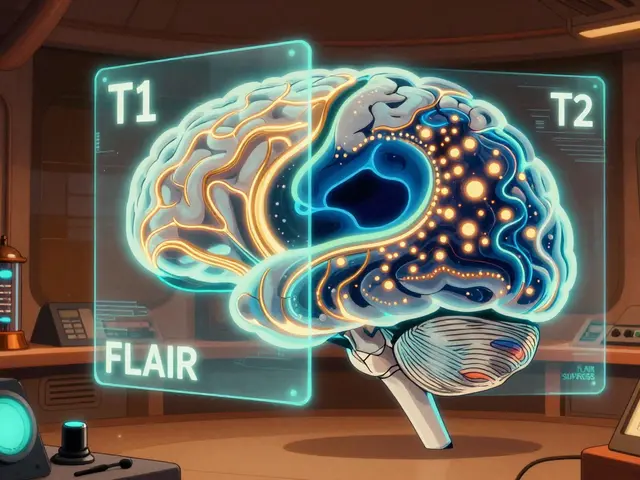

How It Works: Blocking Cyclooxygenase

Ketorolac’s magic lies in its interaction with cyclooxygenase enzymes. The body produces two main forms: COX‑1 and COX‑2. COX‑1 maintains stomach lining and platelet function, while COX‑2 spikes during inflammation.

Ketorolac is a non‑selective COX inhibitor-it blocks both COX‑1 and COX‑2. By halting prostaglandin synthesis, it reduces inflammation, fever, and the pain signals that stem from tissue injury. This broad inhibition explains its potency but also accounts for the risk of gastric ulcers (COX‑1 blockade) and potential renal effects (reduced renal prostaglandins).

Clinical Use: From the OR to the Outpatient Clinic

Today, ketorolac is administered in three main ways:

- Intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) injection: Used in the immediate postoperative period for rapid analgesia.

- Oral tablets (10mg): Transitioned to once the patient can tolerate oral intake, typically after the first 24hours.

- Topical gel (5%): Emerging for localized musculoskeletal pain, though still less common than oral or injectable forms.

Dosage guidelines are strict: adults get 10‑30mg every 4‑6hours, never exceeding 120mg per day, and the total course must stay under five days. In the elderly or those with compromised kidney function, the max daily dose drops to 60mg.

Clinical scenarios where ketorolac shines include:

- Orthopedic surgeries (knee replacement, spinal fusion) where early mobilization is a priority.

- Dental extractions, especially impacted wisdom teeth, to avoid opioid prescriptions.

- Acute migraine attacks when triptans are contraindicated.

Safety Profile and Controversies

Despite its effectiveness, ketorolac has a reputation for being a double‑edged sword. The most common adverse events are:

- Gastrointestinal bleeding or ulceration (up to 2% of patients in high‑dose regimens).

- Renal impairment, especially in dehydration or pre‑existing kidney disease.

- Bleeding tendency due to platelet inhibition, which can be problematic in patients on anticoagulants.

These risks led to several FDA safety alerts in the 1990s and early 2000s, prompting tighter labeling. In recent years, many hospitals have incorporated ketorolac into multimodal analgesia pathways, pairing it with acetaminophen and regional blocks to minimize opioid use while keeping the duration short.

Ketorolac vs. Ibuprofen: A Quick Comparison

| Attribute | Ketorolac | Ibuprofen |

|---|---|---|

| Potency (analgesic) | ≈ 10× stronger than ibuprofen | Baseline NSAID potency |

| Onset of action | 30min (IV/IM) | 45‑60min (oral) |

| Half‑life | ~5h | ~2h |

| Maximum daily dose | 120mg (5‑day limit) | 2400mg (no strict time limit) |

| Typical use | Short‑term postoperative pain | General mild‑to‑moderate pain, fever |

| Key risks | GI bleed, renal impairment, platelet inhibition | GI bleed (less severe), cardiovascular risk at high doses |

When you need fast, strong pain relief after surgery, ketorolac is the go‑to. For everyday aches or chronic conditions, ibuprofen remains safer for longer courses.

Current Status and Future Directions

Ketorolac is now off‑patent, with dozens of generics flooding the market. Its price has dropped dramatically, making it accessible even in low‑resource settings. However, newer NSAIDs like diclofenac and COX‑2‑selective agents (celecoxib) have carved out niches by offering comparable pain control with a lower GI risk.

Research continues on reformulating ketorolac into prolonged‑release injections and topical gels that might extend its usefulness beyond the five‑day window while mitigating systemic side effects. Some trials are also exploring combination therapy with low‑dose opioids to further cut down opioid consumption.

Bottom Line

From its humble beginnings in a Searle research lab to its status as a staple in operating rooms, ketorolac tromethamine has left an indelible mark on pain management. Its story reminds clinicians that powerful drugs demand respect-use them wisely, monitor patients closely, and always weigh the benefits against the risks.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes ketorolac stronger than other NSAIDs?

Ketorolac binds more tightly to both COX‑1 and COX‑2 enzymes, inhibiting prostaglandin production at lower concentrations. This tighter binding translates into roughly ten times the analgesic potency of drugs like ibuprofen.

Can I take ketorolac if I have a stomach ulcer?

No. Ketorolac’s non‑selective COX inhibition increases the risk of ulcer worsening and bleeding. Patients with active GI ulcers should avoid it and discuss alternatives with their physician.

How long is it safe to stay on ketorolac?

The FDA limits use to five days for most adults. Extending beyond that markedly raises the chance of serious GI or renal complications.

Is ketorolac available without a prescription?

In the United States and many other countries, ketorolac is prescription‑only due to its potency and safety profile. Some nations may allow low‑dose tablets over the counter, but a doctor’s guidance is strongly recommended.

What are the alternatives for short‑term postoperative pain?

Alternatives include IV acetaminophen, regional nerve blocks, low‑dose morphine, or COX‑2‑selective NSAIDs like celecoxib. The choice depends on the surgery type, patient comorbidities, and bleeding risk.

Alyssa Griffiths

Ketorolac’s rise wasn’t just a happy accident, it was a calculated maneuver by big pharma, disguised as scientific progress, and the 1989 FDA approval was fast‑tracked thanks to back‑room lobbying, many don’t realize that the “non‑opioid miracle” narrative conveniently obscures the profit motive, the drug’s COX‑non‑selectivity was emphasized to hide its GI risks, and the restriction to five days was barely a suggestion in the original label drafts, a classic case of regulatory capture, don’t be fooled by the glossy marketing brochures!

dany prayogo

Ah, the glossy hype about Ketorolac – truly a masterpiece of medical hype, because nothing says "cutting‑edge" like a drug that mirrors morphine’s potency while demanding a guilt‑laden instruction manual, let’s dissect the so‑called "short‑term miracle": first, the half‑life of roughly five hours sounds convenient until you remember it forces a dosing schedule that eclipses patient compliance; second, the claim of “rapid onset” is merely a marketing buzzword, the 30‑minute window is practically a snooze for the peri‑operative staff, who end up juggling IV lines; third, the touted “lower sedation” is a double‑edged sword, hiding the fact that patients may experience subtle cognitive fog that goes unreported; fourth, the risk profile – gastrointestinal bleeding, renal impairment, platelet inhibition – is shoved into fine print, making the drug a ticking time‑bomb for anyone with comorbidities; fifth, the five‑day limit is a regulatory compromise, not a scientific certainty, and clinicians often push it to the brink, ignoring the escalating risk curve; sixth, the comparison with ibuprofen in the table is a straw‑man, because ibuprofen is not intended for surgical pain at all; seventh, the surge in multimodal protocols now sidelines Ketorolac, proving that its reign was more of a fleeting fad than a lasting breakthrough; eighth, the “non‑opioid” label conveniently sidesteps the opioid crisis narrative, positioning Ketorolac as a scapegoat‑free hero while the reality is more nuanced; ninth, the drug’s inclusion in prescribing guidelines often reflects institutional inertia rather than robust evidence; tenth, the pharmaceutical companies continue to push generic versions, banking on brand‑agnostic prescribing patterns; eleventh, the “rapid ambulation” benefit is overstated – early mobilization depends on surgical technique and rehab, not solely on analgesia; twelfth, the notion that Ketorolac reduces opioid consumption is true only when paired with strict protocols, otherwise you just replace one risk with another; thirteenth, the lack of a COX‑2‑selective profile increases cardiovascular concerns that are rarely discussed; fourteenth, the historical narrative omits the lobbying efforts in the late ’80s that paved the way for approval; fifteenth, let’s not forget the countless case reports of acute renal failure that still surface in the literature, a reminder that the drug isn’t a harmless panacea.

Wilda Prima Putri

Ketorolac can be a real game‑changer when used wisely, but you still need to watch the clock and the kidneys.

Sharif Ahmed

One must appreciate the theatricality of Ketorolac’s entry onto the stage of modern analgesia; its debut was heralded with fanfare akin to a celebrity’s red‑carpet arrival, yet beneath the glitter lay a paradoxical beast, simultaneously a saviour and a siren; the drug’s potency, equivalent to a tenth of morphine’s strength, cast it as the understudy ready to replace the opioid lead, but the script was riddled with scenes of gastrointestinal peril and renal distress; the dramatic tension escalates as clinicians, driven by the desire for swift pain relief, overlook the lingering shadow of bleeding risk; the narrative is further complicated by the pharmaceutical chorus, singing praises while the regulatory director whispers cautions about five‑day limits; in the end, the drama of Ketorolac is a cautionary tale – a reminder that brilliance in pharmacology is often accompanied by a tragic flaw, demanding respect, vigilance, and an unapologetic adherence to safety protocols.

Chelsea Kerr

Ketorolac’s mechanism-non‑selective COX inhibition-means it hits both the pain pathways and the protective prostaglandins, so while it’s powerful, we must balance efficacy with safety. 🌟 Think of it as a double‑edged sword: you get rapid relief, but you also invite GI and renal concerns if you stay beyond the recommended window. 🩺 In practice, pairing a short course of Ketorolac with a proton‑pump inhibitor can mitigate the ulcer risk, and close monitoring of creatinine keeps the kidneys happy. 👍 Always tailor the dose to the patient’s age and comorbidities, and never exceed the five‑day limit.

Tom Becker

look, the "secret" is that big pharm pushed ketorolac as the opex fix while hiding the bleed risks, i’ve seen patients end up in the er for GI bleeds cuz doc forgot the ppi, its not a miracle drug, its a double‑edged sword, stay woke.

Laura Sanders

ketorolac is way stronger than ibuprofen and works fast but you gotta keep an eye on your stomach and kidneys, especially if you have any pre existing issues.

Jai Patel

Absolutely! 🎉 In my experience, a short burst of Ketorolac right after orthopedic surgery can jump‑start mobilization, but remember to balance it with acetaminophen and maybe a regional block for that perfect multimodal cocktail. 🌈 Just don’t let anyone think it’s a free pass to ignore the renal warnings – stay hydrated and monitor labs!

Zara @WSLab

Ketorolac really shines in the immediate postoperative period, giving patients the boost they need to start moving early; just be sure to transition to something gentler for longer‑term pain.

Randy Pierson

While Ketorolac’s rapid onset is impressive, the need for vigilant monitoring can’t be overstated – a quick check of renal function and a prophylactic PPI should become routine steps in any postoperative protocol.

Bruce T

People love to hype up Ketorolac as the ultimate non‑opioid, but let’s not forget it’s still an NSAID with serious side effects, so treat it with the same caution you’d give any potent drug.

Darla Sudheer

Exactly, moderation is key – short courses, proper dosing, and patient education go a long way in keeping things safe.

Elizabeth González

The ethical considerations surrounding Ketorolac’s prescription reflect broader tensions in modern medicine, where therapeutic efficacy must constantly be weighed against potential harm.

Sebastian Samuel

😈 Let’s cut to the chase – Ketorolac is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, promising fast relief while quietly setting the stage for hidden bleeds and silent kidney damage, especially when doctors get complacent.

Mitchell Awisus

Indeed, the pharmacological profile of Ketorolac is a double‑edged sword, offering potent analgesia at the expense of inhibiting protective prostaglandins; consequently, clinicians must adopt a balanced approach that includes vigilant monitoring, prophylactic gastro‑protective agents, and strict adherence to the five‑day limit, otherwise the short‑term benefits quickly give way to serious adverse outcomes.

Annette Smith

Balance is essential.

Write a comment