Endocrine Disorder & Bone Health Checker

Analysis Results

Enter your lab values and click "Analyze My Bone Health Profile" to get insights into possible endocrine disorders affecting your bone health.

Quick Take

- Osteodystrophy is a bone‑growth problem that often signals a hormone issue.

- Key hormones - parathyroid hormone, thyroid hormone, cortisol, and insulin - directly steer calcium and phosphate balance.

- Both over‑active and under‑active endocrine glands can lead to the same bone‑weakening patterns.

- Renal osteodystrophy is the textbook case of kidney‑linked endocrine disruption.

- Early labs and targeted hormone therapy can halt or even reverse bone damage.

When you hear the word osteodystrophy, you might picture a rare bone disease that sits alone in a medical textbook. In reality, it’s often a symptom of a deeper hormonal imbalance. This guide pulls apart the web of connections between bone‑weakening disorders and the endocrine system, giving you a clear picture of why doctors chase hormone labs when patients show up with fragile bones.

What Is Osteodystrophy?

osteodystrophy, a disorder of bone growth and mineralization that reflects systemic problems such as kidney disease, hormonal imbalance, or chronic inflammation isn’t a single disease. It’s a umbrella term for any condition where bone tissue fails to mature correctly, leading to soft, pliable, or abnormally dense bone. The hallmark signs are low bone mineral density, abnormal radiographic patterns, and frequent fractures despite minimal trauma.

The word itself combines “osteo” (bone) and “dystrophy” (abnormal development). Clinically, doctors split osteodystrophy into two major camps: metabolic (linked to mineral handling) and endocrine (linked to hormone signaling). The metabolic side often overlaps with the endocrine side, because hormones are the master regulators of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D - the three pillars of bone health.

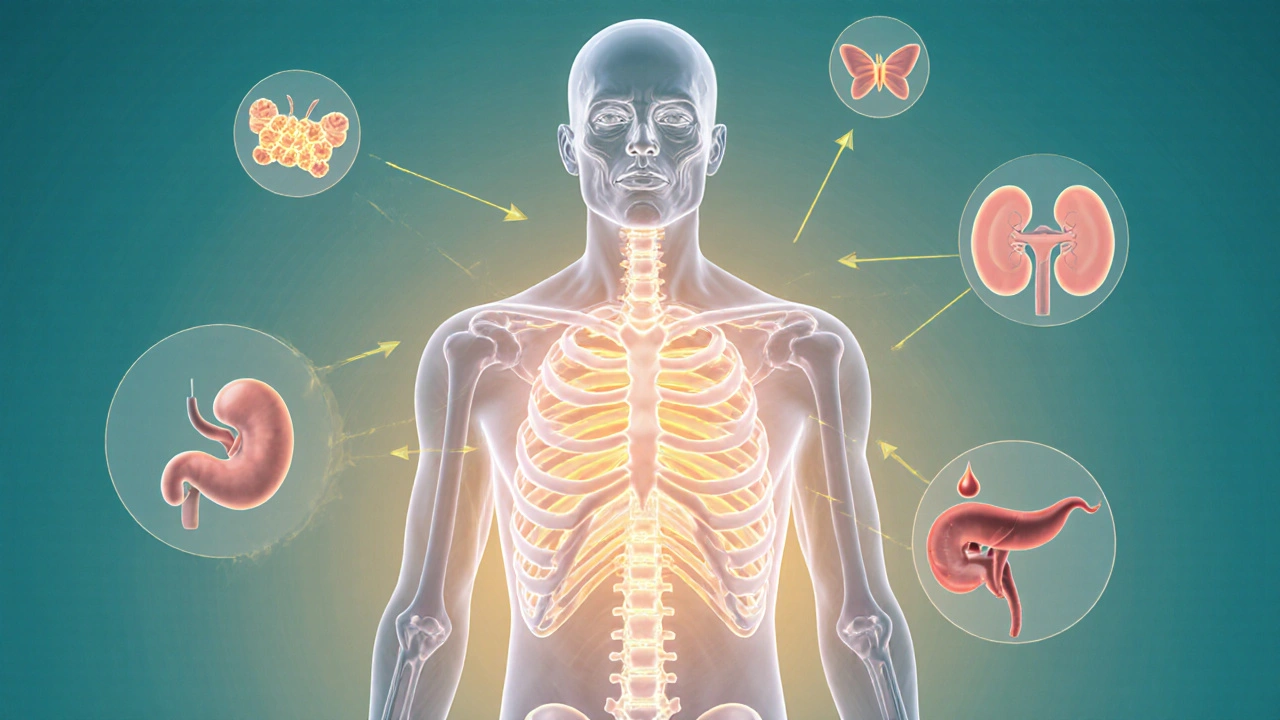

Endocrine Disorders That Touch Bone Metabolism

endocrine disorder, a condition where hormone production or action is abnormal, affecting organs throughout the body can tip the delicate balance that keeps bone strong. When hormones either surge or drop, they change how much calcium gets absorbed from food, how much gets re‑absorbed in the kidneys, and how fast bone cells lay down new matrix.

The most common culprits include:

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH) excess or deficiency

- Thyroid hormone imbalance (hyper‑ or hypothyroidism)

- Cortisol overproduction (Cushing’s syndrome) or deficiency (Addison’s)

- Insulin resistance and chronic hyperglycaemia (type 2 diabetes)

- Sex‑hormone deficits (low estrogen or testosterone)

Each of these alters the trio of calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D - the three variables that dictate whether bone tissue stays solid or turns into a spongy scaffold.

Hormonal Pathways Linking Glands to Bones

Understanding the biology helps explain why an overactive thyroid can feel like a ticking time bomb for your skeleton.

- parathyroid hormone, a key regulator that raises blood calcium by stimulating bone resorption, enhancing kidney re‑absorption, and activating vitamin D. When PTH spikes (primary hyperparathyroidism), bone loses calcium faster than it can be replaced, causing osteodystrophic changes.

- vitamin D, a fat‑soluble hormone that boosts intestinal calcium absorption and works hand‑in‑hand with PTH. Deficiency reduces calcium uptake, prompting secondary PTH rise and bone loss.

- thyroid hormone, a metabolic accelerator that increases bone turnover; excess speeds up resorption, deficiency slows remodeling. Both extremes can result in weakened bone architecture.

- cortisol, a catabolic steroid that suppresses osteoblast activity and enhances osteoclast lifespan. Chronic high cortisol (Cushing’s) shrinks bone‑forming cells, leading to osteopenia and eventually osteodystrophy.

- insulin, a growth‑promoting hormone that also stimulates osteoblasts; insulin resistance blunts this effect. Diabetes is linked to low bone turnover and micro‑vascular damage, compounding fracture risk.

These pathways intersect. For example, high cortisol can blunt vitamin D activation, while excess PTH can suppress sex hormones. The net result is a cascade that reshapes bone tissue.

Common Endocrine Disorders That Trigger Osteodystrophy

The table below condenses the most frequently seen endocrine conditions and how each derails normal bone remodeling.

| Disorder | Key Hormonal Change | Effect on Calcium/Phosphate | Typical Bone Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Hyperparathyroidism | Elevated PTH | ↑ serum Ca, ↓ PO4 | Subperiosteal bone resorption, brown tumours |

| Hypoparathyroidism | d>Low PTH | ↓ serum Ca, ↑ PO4 | Basal ganglia calcifications, increased bone density |

| Hyperthyroidism | Excess T3/T4 | ↑ bone turnover, transient hypercalcaemia | Osteopenia, thin cortical bone |

| Hypothyroidism | Low T3/T4 | ↓ bone turnover, normal Ca | Increased bone mass but poor quality |

| Cushing’s Syndrome | Excess cortisol | ↓ Ca absorption, ↑ urinary Ca loss | Rapid loss of trabecular bone, vertebral fractures |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Insulin resistance | Normal Ca, impaired bone formation | Higher fracture risk despite normal BMD |

| Hypogonadism (low estrogen/testosterone) | Reduced sex steroids | ↓ osteoblast activity, ↑ resorption | Post‑menopausal‑type osteoporosis, low BMD |

Notice how each disorder nudges the calcium‑phosphate set point in a different direction. The body’s attempt to compensate-usually by tweaking PTH-creates a feedback loop that either erodes bone or forces it into a brittle over‑mineralized state.

Renal Osteodystrophy - The Classic Case Study

renal osteodystrophy, a bone disorder that arises from chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the resulting secondary hyperparathyroidism showcases the endocrine‑bone link like nothing else.

Kidneys have three jobs for bone health:

- Convert inactive vitamin D to its active form (calcitriol).

- Excrete excess phosphate.

- Regulate calcium re‑absorption.

When CKD strikes, phosphate builds up, calcitriol drops, and calcium falls. The parathyroid glands swing into overdrive, flooding the bloodstream with PTH. This cascade drives bone resorption, leading to the characteristic mixed picture of high‑turnover (osteitis fibrosa) and low‑turnover (adynamic) bone lesions. If you ever see a patient on dialysis with bone pain and a shaky X‑ray, renal osteodystrophy is often the hidden culprit.

Diagnosing the Bone‑Endocrine Axis

Lab work is the first stop. A typical panel includes:

- Serum calcium (total and ionized)

- Serum phosphate

- Intact PTH

- 25‑hydroxy‑vitamin D

- Thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) and free T4

- Morning cortisol (and ACTH if Cushing’s is suspected)

- HbA1c or fasting glucose for diabetes evaluation

Imaging rounds out the picture. Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) gives a bone mineral density (BMD) score, but it won’t reveal turnover rates. For that, clinicians rely on bone turnover markers (alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin) or a bone biopsy in rare cases.

The key is to match the biochemical pattern with the radiographic signs. High PTH + low calcium = hyperparathyroid osteodystrophy. Low calcium + low PTH = hypoparathyroid bone calcifications. Normal calcium but high cortisol points toward Cushing‑related loss.

Managing Osteodystrophy When Hormones Are Off‑Balance

Treatment follows two parallel tracks: fix the hormone problem and protect the bone.

- Address the primary endocrine disorder - surgical removal of a parathyroid adenoma, anti‑thyroid meds for hyperthyroidism, cortisol‑lowering agents for Cushing’s, or insulin sensitizers for diabetes.

- Supplement the downstream effectors - calcium (1,000‑1,200mg/day), vitamin D3 (800‑1,000IU/day), or active calcitriol in CKD.

- Use anti‑resorptive drugs sparingly. Bisphosphonates can curb bone loss but may worsen adynamic bone disease in renal patients.

- Consider anabolic therapy (teriparatide) when low bone formation is the main issue, but only after PTH levels are stabilized.

- Encourage lifestyle steps - weight‑bearing exercise, smoking cessation, and moderate alcohol.

Regular monitoring is vital. Re‑check labs every 3‑6months after therapy changes, and repeat DXA every 1‑2years to gauge response.

Putting It All Together

Osteodystrophy is rarely a mystery disease; it’s a symptom screaming that the endocrine system is out of sync. By tracing calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D back to their hormonal puppeteers, clinicians can pinpoint the root cause and intervene before the skeleton suffers irreversible damage.

If you suspect an endocrine driver behind bone pain or fractures, start with a focused hormone panel, interpret the results in the context of the table above, and tailor treatment to both the gland and the bone. The sooner the hormonal imbalance is corrected, the better the chance of restoring healthy bone turnover.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can osteodystrophy be reversed?

Yes, in many cases. When the underlying hormonal disturbance is treated-whether it’s parathyroid surgery, thyroid medication, or improved diabetes control-bone turnover can normalize and some lost density can be regained, especially with adjunctive calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Why does kidney disease cause bone problems?

Kidneys activate vitamin D, excrete phosphate, and fine‑tune calcium re‑absorption. Chronic kidney disease disrupts all three, leading to phosphate retention, low active vitamin D, and secondary hyperparathyroidism - the perfect storm for renal osteodystrophy.

Is high cortisol always bad for bone?

Prolonged excess cortisol suppresses osteoblasts and increases bone resorption, dramatically raising fracture risk. Short‑term spikes (e.g., stress) have a smaller impact, but chronic Cushing’s syndrome is clearly detrimental.

Do diabetic patients need bone density scans?

Even with normal DXA scores, type 2 diabetes raises fracture risk due to poor bone quality. Many endocrinologists now recommend a baseline scan and periodic follow‑up, especially if other risk factors coexist.

What’s the difference between osteodystrophy and osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a primary loss of bone mass, usually age‑related. Osteodystrophy, on the other hand, signals a secondary cause-most often a hormonal or metabolic disorder-behind abnormal bone remodeling.

Becky B

Ever notice how every new health guideline seems to slip in just as the big pharma lobbyists get a fresh round of campaign cash? They push calcium supplements like candy while quietly downplaying the role of hormone imbalance in bone loss. The whole osteodystrophy thing is a perfect smokescreen – they want you to blame diet, not the hidden endocrine sabotage. Stay vigilant, question the sources, and demand real transparency.

Aman Vaid

The relationship between endocrine dysfunction and osteodystrophy is fundamentally mediated by calcium‑phosphate homeostasis, which is regulated by a tightly controlled hormonal axis. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) elevates serum calcium by stimulating osteoclastic resorption, increasing renal calcium reabsorption, and activating 1‑α‑hydroxylase to produce calcitriol. Vitamin D, in its active form, enhances intestinal calcium absorption and works synergistically with PTH to maintain extracellular calcium levels. When PTH is chronically elevated, as in primary hyperparathyroidism, the net effect is accelerated bone turnover leading to subperiosteal resorption and brown tumours, classic features of osteodystrophy. Conversely, hypoparathyroidism produces hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia, which can paradoxically increase bone density but impair mineralization, resulting in ectopic calcifications. Thyroid hormones modulate basal metabolic rate and directly influence osteoblast and osteoclast activity; hyperthyroidism increases bone remodeling velocity, often outpacing formation and causing osteopenia, whereas hypothyroidism slows turnover, yielding structurally weak bone despite higher mass. Cortisol exerts catabolic effects on bone by suppressing osteoblast differentiation and extending osteoclast lifespan; chronic excess cortisol, as observed in Cushing’s syndrome, precipitates rapid trabecular loss and vertebral fractures. Insulin resistance, a hallmark of type 2 diabetes, impairs osteoblast function through inflammatory cytokine pathways, contributing to a phenotype of normal bone mineral density but reduced material strength. Additionally, sex steroid deficiency, particularly estrogen loss in post‑menopausal women, removes the protective anti‑resorptive effect, predisposing to cortical thinning. Renal osteodystrophy epitomizes the endocrine‑bone nexus: failing kidneys cannot excrete phosphate, activate vitamin D, or reabsorb calcium efficiently, prompting secondary hyperparathyroidism and mixed high‑ and low‑turnover bone lesions. Laboratory evaluation therefore requires a comprehensive panel: serum calcium, phosphate, intact PTH, 25‑hydroxy‑vitamin D, TSH, free T4, morning cortisol, and fasting glucose or HbA1c. Interpretation of these results must consider the feedback loops; for example, elevated PTH with low calcium suggests primary hyperparathyroidism, whereas high calcium with suppressed PTH points toward hyperthyroidism or malignancy. Imaging, including dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry and, when indicated, bone turnover markers, complements biochemical data to stratify fracture risk. Therapeutically, correcting the underlying endocrine abnormality-parathyroidectomy, anti‑thyroid medication, glucocorticoid antagonists, or optimized glycemic control-stabilizes bone remodeling, and adjunctive calcium/vitamin D supplementation supports mineralization. Early intervention, coupled with lifestyle measures such as weight‑bearing exercise and smoking cessation, maximizes the potential for bone regeneration and reduces long‑term morbidity.

xie teresa

Reading through this guide reminded me how interconnected our systems really are, and that a simple lab panel can unveil a hidden hormonal culprit behind bone pain. It’s comforting to know that addressing the root endocrine issue often restores bone health, rather than just masking symptoms. Thanks for breaking it down in such a clear way.

Srinivasa Kadiyala

While the guide is thorough, one could argue that the emphasis on labs overlooks lifestyle nuances, such as dietary phytates and chronic stress, which also modulate calcium metabolism; moreover, not every patient will fit neatly into the textbook patterns, so clinicians should keep a broader differential in mind; still, the biochemical framework remains indispensable, no doubt.

Alex LaMere

Labs speak louder than myths. 🧪

Dominic Ferraro

What a powerful reminder that our bodies are capable of healing when we give them the right cues! By targeting the hormonal imbalance first, we set the stage for bone cells to rebuild, and every step-whether it's a calcium supplement or a well‑timed thyroid medication-adds a brick to a stronger skeleton. Keep pushing for that holistic approach; the results are worth the effort.

Jessica Homet

Sure, but half the time patients get bombarded with supplements and never see a real endocrine work‑up, ending up with more confusion than clarity. The guide could stress that before you start popping pills, get that hormonal panel sorted.

mitch giezeman

Spot on! If you’re tracking your labs, look for a pattern: high PTH with low calcium points to primary hyperparathyroidism, while low PTH with high calcium may hint at malignancy or vitamin D toxicity. Pair that with a DXA scan, and you’ll have a solid baseline to monitor treatment response.

Kelly Gibbs

Interesting read, definitely something to keep in mind when reviewing patient charts.

KayLee Voir

Great summary! Remember, patients often feel overwhelmed, so breaking down each hormone’s role into bite‑size pieces can really empower them to stick with treatment plans.

Bailey Granstrom

Endocrine chaos = bone catastrophe!

Melissa Corley

lol i think they overcomplicate it 😂 these bones are strong enough unless you drink 10 coffees a day... but yea, hormones matter tho 🦴

Kayla Rayburn

Appreciate the balanced view-reminding clinicians to consider both labs and patient lifestyle creates a more comprehensive care plan.

Dina Mohamed

Absolutely, the cascade-from parathyroid hormone, through vitamin D activation, to calcium re‑absorption, is a beautifully orchestrated process, and when any note is off‑key, the entire skeletal symphony can falter, so early detection and targeted therapy are paramount, allowing the body to regain its harmonious rhythm.

Kitty Lorentz

i get that hormones are key but sometimes the labs are confusing try to keep it simple and listen to how the patient feels its not all numbers

inas raman

Let’s take this knowledge and turn it into action! Grab those labs, talk to your doc, and start building stronger bones today-your future self will thank you.

Jenny Newell

While the exposition is extensive, the reliance on dense endocrinological lexicon may alienate primary care practitioners seeking pragmatic algorithms for osteodystrophic assessment.

Kevin Zac

Good point-translating the pathway into a step‑by‑step flowchart, highlighting key thresholds for calcium, phosphate, and PTH, would make the information more actionable for front‑line clinicians.

Stephanie Pineda

Isn't it fascinating how the skeleton can be seen as a diary of our internal chemistry? Each fracture tells a story of hormonal whispers or shouts, and by listening closely we rewrite the narrative toward resilience.

Write a comment