When a hospital decides to add a generic drug to its formulary, it’s not just about cost. It’s about safety, supply, clinical outcomes, and the hidden economics behind every pill on the shelf. Hospitals don’t pick generics because they’re cheap-they pick them because they’ve been vetted, tested, and proven to work in real hospital settings. And that process is far more complex than most people realize.

What Is a Hospital Formulary, Really?

A hospital formulary isn’t just a list of approved drugs. It’s a living, breathing system managed by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee. This group-made up of pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and sometimes administrators-meets monthly or quarterly to review new drugs, remove underperforming ones, and decide which generics make the cut. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) calls it a clinical governance tool, not a purchasing department. That’s key. This isn’t procurement. It’s patient care.Most hospitals use closed or partially closed formularies, meaning only drugs on the list can be routinely ordered. About 78% of academic medical centers operate this way, compared to just 42% of commercial health plans. Why? Because hospitals need control. In an ICU, you can’t let a nurse grab whatever’s cheapest off the shelf. You need predictable dosing, reliable supply, and proven safety.

The Tier System: How Generics Are Ranked

Hospital formularies use tiers to guide prescribing. Think of it like a pricing ladder, but with clinical rules attached.- Tier 1: Preferred generics. Lowest cost to the hospital, no prior authorization needed. These are the workhorses-metformin, lisinopril, amoxicillin.

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics or preferred brands. Slightly higher cost, may require documentation.

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brands. Expensive. Only used if generics fail or aren’t suitable.

- Tiers 4-5: Specialty drugs. High-cost, complex therapies. Rarely generics, often biologics.

Generics dominate Tier 1. In 2022, generics made up 89% of hospital drug purchases by volume-but only 28% of spending. That’s the economic engine behind formulary decisions. But here’s the catch: the lowest list price doesn’t always mean the lowest net cost.

It’s Not Just FDA Approval

Many assume if the FDA approves a generic, it automatically goes on the formulary. That’s not true. The FDA says a generic is bioequivalent. The P&T committee asks: Is it clinically equivalent?For simple pills-like generic atorvastatin-that’s usually a yes. But for complex generics? Not so fast. Inhalers, injectables, topical creams, and transdermal patches have delivery mechanisms that matter. A 2022 FDA report found only 62% of complex generic applications were approved on the first try, compared to 88% for standard ones. That gap creates real problems in hospitals.

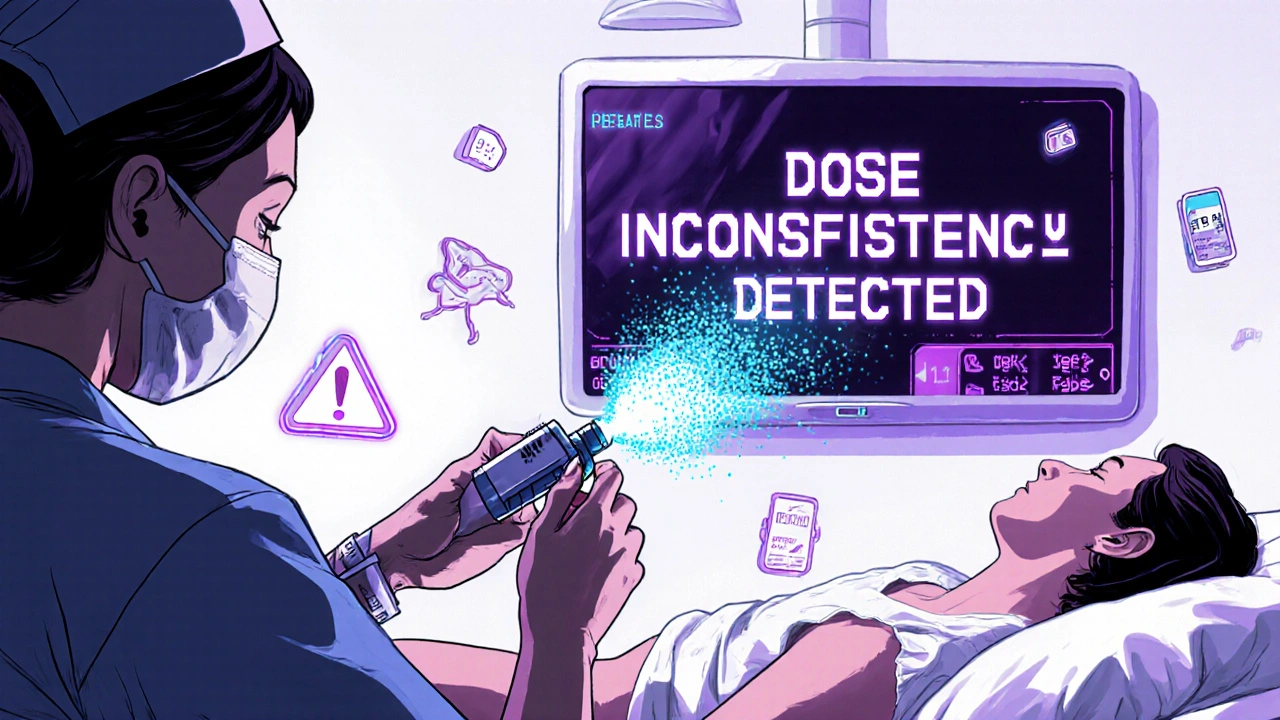

Dr. John Smith, chair of the P&T committee at UCSF Medical Center, put it plainly: “In critical care, tiny differences in absorption can mean the difference between a stable patient and a code blue.” A generic epinephrine auto-injector might have the same active ingredient, but if the spray pattern or dose consistency is off, it could fail when a nurse needs it most.

The Hidden Economics: Rebates, Contracts, and Supply Chains

The biggest myth about hospital generics? That price is the only factor. It’s not.Manufacturers now offer rebates, service agreements, and volume discounts that aren’t visible on the invoice. Dr. Emily Chen at Massachusetts General Hospital says, “We’ve seen generics with the lowest list price end up costing more after rebates are clawed back or service fees are added.”

Then there’s the 340B Drug Pricing Program. It lets safety-net hospitals buy generics at steep discounts. But here’s the twist: hospitals that qualify for 340B often stock different generics than those that don’t. That creates fragmentation. One hospital might use Generic A because of its 340B deal; another, down the street, uses Generic B because it’s cheaper without the program. Both are FDA-approved. Both work. But they’re not interchangeable.

And supply? It’s a nightmare. In Q3 2023, 84% of hospital pharmacists reported at least one critical generic shortage. When a Tier 1 generic runs out, hospitals are forced to buy non-formulary alternatives-at 3-5x the price. One hospital in Ohio paid $42 per vial for a generic antibiotic that normally cost $3.50. That’s not savings. That’s financial damage.

Real-World Impact: When Generics Go Wrong

There are success stories. Mayo Clinic saved $1.2 million a year by switching to generic cardiovascular meds-with tight monitoring protocols. Cleveland Clinic cut generic acquisition costs by 18.3% without harming outcomes.But there are also failures. At Johns Hopkins, switching from brand to generic anticoagulants led to unexpected bleeding events. Why? Subtle differences in how the drug was absorbed. Nurses had to spend extra time checking INR levels. The cost savings vanished in labor hours.

A 2023 survey of 1,247 hospital pharmacists found 68% struggled with therapeutic equivalence for complex generics-especially inhalers and IV solutions. One pharmacist described a generic albuterol inhaler that felt “different” to patients. It worked, but patients reported less relief. Compliance dropped. The hospital had to revert to the brand.

What It Takes to Get It Right

Successful formularies don’t happen by accident. They require:- At least 50% clinical pharmacist representation on the P&T committee

- Quarterly reviews of new generics within 90 days of FDA approval

- Formal AMCP dossiers-detailed submissions with clinical studies, pharmacology, and cost analyses

- Integration with electronic health records (EHRs) to flag non-formulary orders

But here’s the problem: only 37% of hospitals have automated formulary alerts in their EHRs. That means 63% rely on doctors and nurses to remember the rules. And when they forget? 15-20% of orders violate formulary policy, according to a University of Michigan study.

The Future: Transparency, Complexity, and Personalized Medicine

Change is coming. The 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act requires full pricing transparency for generics by January 2025. That means hospitals will finally see the true net cost-rebates, fees, and all. That could shift decisions away from rebate-driven choices and back to clinical value.The FDA’s GDUFA III program is investing $4.3 million annually to speed up approval of complex generics. By 2026, we may see more generics for injectables, inhalers, and even gene therapies.

And then there’s pharmacogenomics. Twenty-eight percent of academic medical centers now consider genetic data when choosing generics-for example, avoiding a clopidogrel generic in patients with a CYP2C19 mutation. That’s not science fiction. It’s happening now.

But the biggest threat? Drug shortages. In November 2023, the FDA tracked 298 active generic shortages-the highest ever. Hospitals can’t afford to rely on just one supplier. They need flexible formularies that allow for rapid substitution without compromising safety.

Bottom Line: Generics Are a Tool, Not a Shortcut

Hospital formulary economics isn’t about cutting costs. It’s about managing risk. Choosing a generic isn’t a transaction. It’s a clinical decision. The right generic, at the right time, with the right monitoring, saves money and lives. The wrong one-even if it’s cheaper-can cost more in the long run.When a hospital adds a generic to its formulary, it’s betting on safety, consistency, and reliability. And that’s worth more than any rebate.

How do hospitals decide which generic drugs to include on their formulary?

Hospitals use a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee to evaluate generics based on three core factors: clinical efficacy, safety, and cost. They don’t rely solely on FDA approval. Instead, they review bioequivalence data, real-world outcomes, supply reliability, and whether the drug fits the hospital’s patient population. Complex generics-like inhalers or injectables-require additional testing for delivery consistency and clinical performance.

Why can’t hospitals just pick the cheapest generic?

The lowest list price doesn’t always mean the lowest net cost. Many generics come with rebates, service fees, or contractual obligations that only become clear after purchase. A drug might cost $1 per unit on paper, but if the manufacturer requires you to buy 10,000 units or pay for mandatory training, the real cost could be much higher. Hospitals also avoid generics with poor supply records-running out of a critical drug mid-treatment is far more expensive than paying a bit more upfront.

Are all generic drugs the same?

No. While all FDA-approved generics must be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug, that doesn’t mean they behave identically in every patient. Differences in inactive ingredients, manufacturing processes, or delivery systems (like spray patterns in inhalers) can affect how the drug is absorbed or how patients tolerate it. For example, a generic epinephrine auto-injector might deliver the same dose, but if the spray is inconsistent, it could fail during an emergency. That’s why hospitals test generics in real-world settings before approving them.

What role do rebates play in hospital formulary decisions?

Rebates are a major factor, but they’re also a trap. Manufacturers offer financial incentives to get their generics on the formulary. But these rebates are often hidden-tied to volume purchases, service agreements, or performance metrics. Some hospitals have found that a higher-priced generic with a better rebate structure ends up being cheaper than the lowest-list-price option. The 2025 transparency rules will force these costs into the open, likely shifting decisions back toward clinical value.

Why are generic drug shortages such a big problem in hospitals?

Hospitals rely on consistent, reliable supply. When a generic runs out, they can’t wait weeks for a restock. They have to switch to a non-formulary alternative-often at 3 to 5 times the cost. In 2023, 84% of hospital pharmacists reported at least one critical shortage. The top 5 generic manufacturers control nearly 60% of the market, so if one company has a production issue, dozens of hospitals are affected. That’s why formularies now include backup options, even if they’re more expensive.

How do hospitals track whether a generic is working after it’s added?

Hospitals use drug utilization reviews (DUR) to monitor outcomes. Pharmacists track things like readmission rates, lab values (like INR for anticoagulants), adverse events, and compliance. If switching to a generic leads to more side effects or longer hospital stays, the P&T committee will re-evaluate it. Some hospitals even run small pilot programs-switching just one unit to the new generic for 30 days-to test safety before rolling it out hospital-wide.

Is pharmacogenomics changing how hospitals choose generics?

Yes. About 28% of academic medical centers now consider genetic testing data when selecting generics-especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, like warfarin or clopidogrel. If a patient has a genetic variant that makes them a poor metabolizer, a generic version might not work as well. Hospitals are starting to build genetic profiles into their formulary decision tools, so the right drug is chosen based on the patient’s biology, not just cost.

Ryan C

Let’s be real-FDA bioequivalence is a baseline, not a guarantee. I’ve seen generic epinephrine auto-injectors fail in simulation drills because the spray nozzle clogged after 3 months of storage. 🤯 The P&T committee at my hospital runs accelerated stability tests before even considering a new generic. No one wants to be the reason a code blue goes sideways because we saved $0.40 per vial.

Dan Rua

This is such an important thread. I’ve worked in 3 different hospitals, and the formulary process is way more nuanced than most people think. The rebates thing? Totally true. We once picked a generic because it had a 15% rebate, only to find out the manufacturer required us to use their proprietary EHR module. Cost? More than the brand. 😅

Mqondisi Gumede

Who cares about all this corporate nonsense. In South Africa we just use what works and what we can get. Hospitals here dont have 10 pharmacists in a room debating inhalers. We use the cheapest thing that doesnt kill people. You guys overthink everything. Its just medicine. Stop making it a finance seminar

Douglas Fisher

Wow. This is so important. I just want to say, thank you for writing this. I’ve been in the trenches for 12 years, and I’ve seen the exact same things happen-especially with the 340B program. The fragmentation is real. And the shortages? They’re not just inconvenient-they’re dangerous. I’m so glad someone’s finally putting this out there. 🙏

Albert Guasch

It is imperative to underscore that the hospital formulary is not a fiscal instrument, but rather a clinical governance mechanism predicated upon evidence-based pharmacotherapeutic outcomes. The integration of pharmacogenomic data into formulary decision-making protocols represents a paradigmatic shift toward precision medicine. Moreover, the implementation of automated EHR alerts for non-formulary orders remains an underutilized intervention with demonstrable potential to reduce therapeutic non-adherence by up to 37%.

Ginger Henderson

So… we’re spending millions to avoid a $3 antibiotic that might be ‘slightly less effective’? 😴

Bethany Buckley

It’s fascinating how we’ve elevated the procurement of pharmaceuticals to a quasi-philosophical discourse on ontological equivalence. 🤔 The very notion that a molecule’s therapeutic efficacy can be reduced to a bioequivalence threshold is a triumph of neoliberal reductionism over clinical nuance. And yet-we still trust the same 6 manufacturers to supply 60% of our critical generics? The irony is almost poetic.

Stephanie Deschenes

One thing I’ve learned: the best formularies don’t just pick generics-they build relationships with manufacturers. We have direct contacts at 3 generic suppliers who alert us to potential shortages weeks in advance. It’s not glamorous, but it’s saved us from 4 critical drug crises in the last year. Small efforts, big impact.

Cynthia Boen

This whole post is just corporate fluff. If a generic is FDA approved, it’s fine. Stop overcomplicating things. Nurses aren’t idiots. If the pill looks the same and costs less, give it to the patient. You’re all just protecting your jobs by making this sound like rocket science.

Amanda Meyer

I appreciate the depth here, but I wonder if we’re missing the human element. When a nurse has to explain to a patient why their $3 pill is now $15 because the original generic ran out-it’s not just a cost issue. It’s a trust issue. Maybe the real metric isn’t savings or compliance rates-it’s whether the patient still believes the system has their back.

Write a comment